Resilience (4 of 5): your working identities

Dr Emily Troscianko & Dr Rachel Bray

There are several traps lurking in the realm of work and identity. The first is to believe that we should all know who we are (after all, surely we’ve been alive long enough to have found out?), and that doing things like researching new career possibilities means merely finding ways to put that peerless self-knowledge into practice. Another slightly subtler trap is to believe that there is a ‘real you’ submerged somewhere deep inside, to be uncovered through the hard dredging work of, say, trawling through other people’s LinkedIn profiles and comparing other people’s selves with your own. The myth of a persistent singular ‘me’ is a myth: from the cellular level to the level of values and personality, things are always in flux. As Herminia Ibarra puts it, ‘our working identity is not a hidden treasure waiting to be discovered at the very core of our inner being’ (p. xi). In his recent book The Mind Is Flat (2018), Nick Chater, a professor of behavioural science, marshals a wide range of psychological evidence to demonstrate that ‘the rich mental world we imagine that we are “looking in on” moment-by-moment, is actually a story that we are inventing moment-by-moment’ (p. 14). This doesn’t mean that everything about you is infinitely malleable, just that there is no single ground truth about ‘the real you’ to be unlocked by introspective effort.

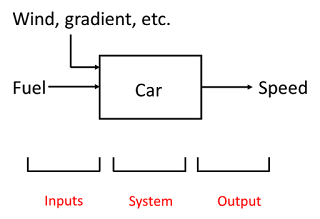

Our identities are numerous, and are always constructed through the interplay between our minds, our bodies, and our social, cultural, and physical environments. Sometimes friction arises between one or more of these. The friction may be productive or not. If it isn’t, it can sometimes be resolved by making changes within the existing system, but sometimes a move to a new context is needed to restore equilibrium (see our earlier post in this series on feedback dynamics between you and academia). However difficult or frightening it is, such a move should never be considered a failure – quite the opposite.

Being alive is a process of iteratively updating our sense of what we are through feedback with what we do and where and how and with whom and with what effects. The looping iterations can be apparently small: move to a new office, realise you’re really enjoying having a far horizon to stare out at, find your mind works differently in different places and experiment with turning this to account by switching places for different tasks. And they can be apparently large: move to a new continent, feel that everything has changed, work out ways to find your feet, discover that the person you are in this place and language is definably different from that person who stepped onto the plane. But sometimes appearances are deceptive: ‘The changes that look the most profound are sometimes in fact the realisation of deeper continuity, while what seems an incremental move can mask a profound shift’ (p. 15). Likewise, every big change also starts small, or ought to: if you’re planning what you expect to be a profound shift, you should almost certainly take some baby steps first, to see how it feels, before your investments of time and energy shift into definite and substantive commitments – and risks.

Conducting modest behavioural experiments on yourself can be a revealing way to do some significant updating of your working model of who you are. For example, maybe you think you’re a night-time person. What happens if for a week you set an early alarm and do an hour of writing before breakfast? Or maybe you’ve always assumed to have to work very long hours because you’re in academia. Next week you’re going to wrap up work before dinner, make plans for your evenings and the weekend, and see what happens. This is about inquiring into who you are (and what it even means to ask the question) by changing what you do, and allowing for one to change as the other does.

Little self-experimentations of this kind can be understood as part of a grander feedback loop for your ‘working identities’, which Ibarra configures as involving transitions between exploring possible selves, lingering between identities, and grounding deep change, which in turn feeds into new explorations. And if the idea of life as feedback loop exhausts you – firstly, well, bad luck. Second, don’t worry, there are outcomes too: forms of external and internal change that are meaningful in their own right, as well as being fodder for the next iteration.

In asking, as we all do from time to time, who am I?, it can be helpful to bear in mind the tendency we have to retreat from action into reflection.

One of the things that tends to happen if we rigidly resist uncertainty is that we make decisions in haste, to get the horribleness of not knowing what comes next out of the way quicker. Retreating from change might mean either staying put or taking the wrong next job or opportunity (especially accepting unsolicited job offers) to ‘stay safe’ (i.e. employed). It might also mean being seduced by the allure of the single big decision that will change everything in one fell swoop. Ibarra’s advice is to ‘Allow yourself a transition period in which it is okay to oscillate between holding on and letting go. Better to live the contradictions than to come to a premature resolution’ (p. 168). In her experience, the process of career change usually takes three to five years. This can feel like forever, but isn’t, and if one tries to short-circuit it, it often just ends up taking longer.

Nothing is ever not changing, but during times of particularly conspicuous change it can be helpful to remember that nothing inherently makes sense or doesn’t, when it comes to our career progression or anything else. Career paths that make sense are just those we manage to put convincing spin on in retrospect.

‘No career change materializes out of the blue. […] Since we are many selves, changing is not a process of swapping one identity for another but rather a transition process in which we reconfigure the full set of possibilities.’ (Ibarra, Working Identity, 2004, p. xi)If you’ve begun to try any of the exercises we suggested in the previous post in this series on resilience, you’ll already understand that exploring your resilience goes right to the heart of who you are.

There are several traps lurking in the realm of work and identity. The first is to believe that we should all know who we are (after all, surely we’ve been alive long enough to have found out?), and that doing things like researching new career possibilities means merely finding ways to put that peerless self-knowledge into practice. Another slightly subtler trap is to believe that there is a ‘real you’ submerged somewhere deep inside, to be uncovered through the hard dredging work of, say, trawling through other people’s LinkedIn profiles and comparing other people’s selves with your own. The myth of a persistent singular ‘me’ is a myth: from the cellular level to the level of values and personality, things are always in flux. As Herminia Ibarra puts it, ‘our working identity is not a hidden treasure waiting to be discovered at the very core of our inner being’ (p. xi). In his recent book The Mind Is Flat (2018), Nick Chater, a professor of behavioural science, marshals a wide range of psychological evidence to demonstrate that ‘the rich mental world we imagine that we are “looking in on” moment-by-moment, is actually a story that we are inventing moment-by-moment’ (p. 14). This doesn’t mean that everything about you is infinitely malleable, just that there is no single ground truth about ‘the real you’ to be unlocked by introspective effort.

Our identities are numerous, and are always constructed through the interplay between our minds, our bodies, and our social, cultural, and physical environments. Sometimes friction arises between one or more of these. The friction may be productive or not. If it isn’t, it can sometimes be resolved by making changes within the existing system, but sometimes a move to a new context is needed to restore equilibrium (see our earlier post in this series on feedback dynamics between you and academia). However difficult or frightening it is, such a move should never be considered a failure – quite the opposite.

Being alive is a process of iteratively updating our sense of what we are through feedback with what we do and where and how and with whom and with what effects. The looping iterations can be apparently small: move to a new office, realise you’re really enjoying having a far horizon to stare out at, find your mind works differently in different places and experiment with turning this to account by switching places for different tasks. And they can be apparently large: move to a new continent, feel that everything has changed, work out ways to find your feet, discover that the person you are in this place and language is definably different from that person who stepped onto the plane. But sometimes appearances are deceptive: ‘The changes that look the most profound are sometimes in fact the realisation of deeper continuity, while what seems an incremental move can mask a profound shift’ (p. 15). Likewise, every big change also starts small, or ought to: if you’re planning what you expect to be a profound shift, you should almost certainly take some baby steps first, to see how it feels, before your investments of time and energy shift into definite and substantive commitments – and risks.

Conducting modest behavioural experiments on yourself can be a revealing way to do some significant updating of your working model of who you are. For example, maybe you think you’re a night-time person. What happens if for a week you set an early alarm and do an hour of writing before breakfast? Or maybe you’ve always assumed to have to work very long hours because you’re in academia. Next week you’re going to wrap up work before dinner, make plans for your evenings and the weekend, and see what happens. This is about inquiring into who you are (and what it even means to ask the question) by changing what you do, and allowing for one to change as the other does.

Little self-experimentations of this kind can be understood as part of a grander feedback loop for your ‘working identities’, which Ibarra configures as involving transitions between exploring possible selves, lingering between identities, and grounding deep change, which in turn feeds into new explorations. And if the idea of life as feedback loop exhausts you – firstly, well, bad luck. Second, don’t worry, there are outcomes too: forms of external and internal change that are meaningful in their own right, as well as being fodder for the next iteration.

In asking, as we all do from time to time, who am I?, it can be helpful to bear in mind the tendency we have to retreat from action into reflection.

Reflection is important. But we can use it as a defense against testing reality; reflecting on who we are is less important than probing whether we really want what we think we want. Acting in the world gives us the opportunity to see our selves through our behaviors and allows us to adjust our expectations as we learn. In failing to act, we hide from ourselves. (Ibarra, p. 168)And if acting is revealing ourselves to ourselves, then the stakes are rather different from what we might tend to assume. The wrong move is not the one that fails to bring the salary increase or the perfect work-life balance. Amongst the people Ibarra interviewed, many of them made mistakes, and struggled with lower income or loss of stimulation. Yet:

I heard great regret only from those who failed to act, who were unable or unwilling to put their dreams to the test and to find out for themselves if there were better alternatives. The only wrong move consisted of no move. (p. 166)Most of it comes back to an acceptance of uncertainty. You may or may not score highly on the Big Five ‘openness to experience’ scale , and it’s not bad not to: patience, routine, and specialised interests are valuable habits and preferences too. But to have any happiness in an uncertain universe, we must accept the inevitability of uncertainty – and all of us will find the level of acceptance we’re able and willing to tolerate.

One of the things that tends to happen if we rigidly resist uncertainty is that we make decisions in haste, to get the horribleness of not knowing what comes next out of the way quicker. Retreating from change might mean either staying put or taking the wrong next job or opportunity (especially accepting unsolicited job offers) to ‘stay safe’ (i.e. employed). It might also mean being seduced by the allure of the single big decision that will change everything in one fell swoop. Ibarra’s advice is to ‘Allow yourself a transition period in which it is okay to oscillate between holding on and letting go. Better to live the contradictions than to come to a premature resolution’ (p. 168). In her experience, the process of career change usually takes three to five years. This can feel like forever, but isn’t, and if one tries to short-circuit it, it often just ends up taking longer.

Nothing is ever not changing, but during times of particularly conspicuous change it can be helpful to remember that nothing inherently makes sense or doesn’t, when it comes to our career progression or anything else. Career paths that make sense are just those we manage to put convincing spin on in retrospect.

Links to all posts in this series:

- Does academic complement or conflict with who you are?

- The feedback dynamics between you and academia

- Distinguishing between assumptions and reality

- Your working identities [this post]

- Having a strategy for cultivating resilience [next post]

For unabridged versions of these posts and full references, check out the Resilience Hub.